The question on everyone's lips at each aerospace gathering these days usually revolves around a simple three-letter acronym – NMA – and what Boeing is going to do about it.

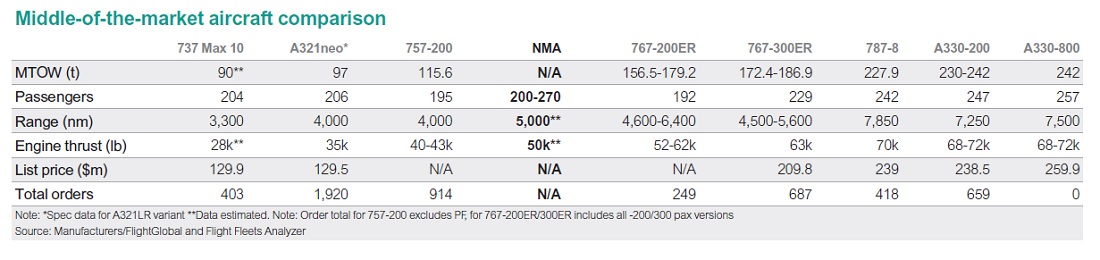

New Mid-market Airplane is the term Boeing applies to its long-running studies for an all-new airliner design to address that difficult segment between the top of the single-aisle sector and the bottom of the widebody market.

Another question being asked is: "What exactly is the NMA?" Defining an aircraft for this sector – dubbed the "middle of the market" or MoM – is tricky because it needs to deliver the economics of a single-aisle but the range and capacity of a small twin-aisle.

"There is an opportunity between the single-aisle and twin-aisle," says Boeing Commercial Airplanes chief executive Kevin McAllister. "That opportunity is an aircraft with 200 to 270 seats and [a range of] up to 5,000nm [9,250km]."

A glimpse of NMA: This impression is based on the only information published by Boeing so far

That's about all Boeing has revealed publicly about the aircraft, other than some fuzzy images. But we know that the NMA will overlap the 737 and 787 families, and there are indications that it is likely to be unconventional in design by the standards of today, possibly with an oval fuselage cross-section incorporating twin-aisle seating.

Boeing's 757 narrowbody did this well in the MoM segment during the 1980s and 1990s, and Airbus now believes it has created the spiritual successor in the shape of the A321LR derivative of the A321neo. And while NMA is often touted as a 757 replacement, it looks more likely to be sized more closely to the 767-200/300 widebody family (below).

Max Kingsley-Jones/FlightGlobal

The A321neo, the largest derivative of the A320neo family, has already outsold the 757's total sales by a more than half. Flight Fleets Analyzer shows that at the end of January Airbus had a backlog for 1,897 A321neos, including 97 LRs.

Even Boeing's head of marketing admits that the Airbus proposition forced it to create another variant of 737 Max. "The Max 10 plugged a hole, as we didn't have as many seats as the A321," says Randy Tinseth.

But now that now there is a larger 737 Max, it's the superior option, he is unsurprisingly quick to claim.

"The beauty of the 737-10 is that it carries the same number of passengers [as the A321], but we have a better, more efficient wing and it is 5,000lb [lighter] than the competition," says Tinseth.

But the market is yet to chime with the Boeing view. Since its launch at the Paris air show last year, Boeing has accumulated 403 Max 10 firm orders, Flight Fleets Analyzer shows.

Boeing concedes that some of these came through conversions by customers of orders for the Max 9, the 737 variant based on the -900ER platform and is larger than the A320 but smaller than the A321. If orders for the Max 9 are included, sales rise to 520.

But deciphering Boeing's orderbook is complex, as Flight Fleets Analyzer also shows another 425 orders where the variant could be either the Max 8 or 9 (or, presumably, the Max 10). Boeing also has more than 870 Max orders where no variant has been declared.

While the Max 10 created a weapon in the Boeing armoury to counter the A321neo family, it is generally viewed as an interim step until the NMA comes along in about seven years' time.

More details on what the NMA actually is are likely to emerge once the Boeing board gives authority to offer. But before that happens, Boeing must convince the board it has a watertight business case and can cost-effectively design, build and sell the aircraft in sufficient numbers to justify the likely $10-15 billion investment it will require to launch.

Speaking at the Singapore air show in February, Tinseth indicated that an early launch decision was unlikely, saying: "In terms of schedule, we're looking at service entry in 2024-2025. That gives us some time."

The big questions that Boeing must answer concern the likely long-term demand, how it will be built, and what the most appropriate engine technology should be to deliver the optimum balance of efficiency, cost and reliability. Part of that latter conundrum will be whether to offer a choice of engine suppliers.

When 757 production ended in 2005, Boeing had delivered 1,049 aircraft. Tinseth sees the NMA market being at least four times that level, putting NMA demand at more than 4,000 units.

But he concedes that identifying the precise market is still a work in progress. "The NMA is probably going to have a bit of a stimulative effect to the market like any new airplane does, so we have to understand what that is," he says.

One of the challenges Boeing faces is that the NMA is not seen as a direct replacement for any current aircraft. This makes nailing down a reliable market forecast even harder.

Flight Ascend Consultancy's long-term market forecast indicates that building a viable business case for NMA "could be challenging", says head of consultancy Rob Morris. However, he adds that "a demand scenario can be painted which could deliver sales that exceed a couple of thousand aircraft over the production life".

Observers are split on whether Boeing will actually launch the programme and, if so, when.

GE Aviation, whose CFM International partnership is seen as a front-runner to power the NMA, expects a launch decision will be needed this year if the target service-entry of the mid-2020s is to be achieved.

"Time is running out," said Chaker Chahrour, GE Aviation's vice-president and general manager of global sales and marketing, during the Aviation Leadership Summit at February's Singapore air show.

"If this is an airplane that wants to enter revenue service in the 2025 timeframe, then we expect there's going to be a decision made sometime this year," he added.

Richard Aboulafia, vice-president of analysis at Teal Group, says it is "a tough call" determining what Boeing will do and when.

"I still think it will be launched this year, but it could easily slip by a year," he says. "There's also a chance Boeing can't make the business case; I'd give that scenario a 15-20% chance."

DVB Bank aviation research chief and managing director Bert van Leeuwen thinks Boeing has talked up the project so much that it cannot turn back now.

"It has positioned itself in a way that it almost 'has to' launch the NMA. Aborting in this phase would be somewhat a loss of face," he says.

Van Leeuwen expects a launch either next year or in 2020. But he thinks the sizing of the aircraft and its integration into other future projects is critical to it being a success.

"I doubt it will be viable on its own as it will require a very expensive new production line. I also believe the NMA must have much in common from both a production and technology perspective with any all-new 737 successor. But that will follow later so as not to cannibalise 737 Max sales."

Airbus for its part does not see a vacant market in the sector that the NMA is aimed at.

"Boeing is trying to position an aircraft in between the 737 and 787, by their own words," says Airbus vice-president of market strategy Bob Lange. "I'm not a believer in magic niches of any type."

Lange believes Boeing is being forced to react to Airbus's success in "carving out a lead" over the 737 with the A320neo family. "And in the 787 segment they've been challenged with the production costs on the smallest model in a market which is quite price-sensitive."

A321LR: Airbus’s secret weapon in battle for the middle of the market?

Airbus

Van Leeuwen concurs on the success of the A320neo family, which could be a thorn in the side of whatever Boeing does.

"Where I see a problem is that Airbus has a very strong position with the A321LR, a very capable aircraft, maybe in combination with the A330neo in certain campaigns," he says.

"The investment in the development of the A320 family as well as the global A320 production and assembly centres has probably been recovered by Airbus a long time ago. So unless the NMA offers hugely lower operational cost – ie, through fuel burn and maintenance costs – Airbus will always be able to offer their A321neo/A321LR or the A330neo at a significantly lower cost."

Aboulafia wonders whether, as a twin-aisle, the NMA could truly compete directly with an A321neo or any future larger derivative.

"Single- and twin-aisles have different operating economics, and different manufacturing costs. Most likely, a Boeing NMA would sell to people who can use this jet to its full capability, about 240-270 seats, and 4,000-5,000nm," he says.

"There's an interesting set of opportunities there, for transatlantic fragmentation, intra-Asia growth, and Middle-East-to-Europe route development, but developing these opportunities would not be the same as countering a large single-aisle head to head."

If NMA goes ahead, as many expect, will Airbus feel compelled to respond with product development? History suggests it will.

In the early 2000s it tried to counter the Boeing's "7E7" (now 787), first with increasingly more complex iterations of the A330 before launching the all-new A350 XWB. Then, about a decade ago, it decided to kill off the threat from the Bombardier CSeries by adopting that aircraft's innovative Pratt & Whitney engine – and also one from CFM – to create the A320neo.

Lange hints that Airbus is ready to react to NMA, saying: "There will be a movement on one side, and we will do what we need to do at the right time to retain our position and to stay competitive."

Flight Ascend Consultancy's Morris says Airbus could have a number of potential options to respond: "A321neo developments, A330neo developments or an all new 'middle-of-the-market' aircraft.... Airbus would have the luxury of responding to whatever Boeing launches and thus would be relatively well positioned."

Van Leeuwen says Airbus could follow an NMA launch "with either an 'A322' stretch of the A321 or an all-new design". He adds: "Some Airbus people that 'should know' already indicated Airbus has an answer ready to the NMA, in case."

When asked at the Singapore air show if Airbus could see any requirement on its product-development horizon for a new 50,000lb-thrust (222.5kN) engine being planned for NMA, the company's new chief salesman, Eric Schulz, replied: "Potentially maybe."

So one response scenario could be an "A322" stretch – perhaps with a larger wing to boost performance and fuel capacity – powered by any new turbofan developed for NMA.

"If Boeing doesn't launch the NMA, it will lose a few points in market share, but on the other hand it will save $12-15 billion in nonrecurring costs," says Aboulafia. "That could be used to more aggressively discount the 737 Max 10, but that wouldn't stop the A321neo from controlling the segment."

The other key NMA questions are around the powerplant: how many choices will be offered on the airframe and what technologies will they incorporate.

Tinseth confirms that Boeing has received proposals from CFM, Pratt & Whitney and Rolls-Royce and says "they're all coming at the challenge in slightly different ways". However, he declines to elaborate on the technology and on whether the programme will be structured as sole-source.

GE Aviation's Chahrour says CFM has all but ruled out a geared-fan design, and its offering is likely to be based on a direct-drive configuration like today's Leap engine that powers the 737 Max and A320neo.

P&W, like R-R, declines to comment specifically on plans for the NMA but is widely assumed to have based its submission on the geared-turbofan architecture it introduced with its PW1000G engine family.

R-R points to its Advance direct-drive engine design for the first half of the 2020s and the UltraFan geared design which will be available from 2025.

"The only engine OEM that can, or would, insist upon sole-source is GE, but it's far from clear that GE still has that kind of financial clout," says Aboulafia. "If GE doesn't have the money needed to buy this platform, NMA will likely have a choice of two engines."

Morris is not convinced the expected volume of sales could justify all-new engine programmes at more than one OEM. But any competitive response from Toulouse could change the market dynamics, both from an airframe perspective and for the powerplants. And If Airbus does decide to respond with a product that uses the NMA's engines, it would thus perhaps enhance the business case for more than one engine option, he adds.

Time will tell whether 2018 will be the year of the NMA. But what is certain is that every day that passes, the Airbus sales team is running at full chat to ratchet up the orderbook for the A321LR.

Source: Airline Business